|

1917: Time Hill | |

|

With their continuing success, the Gruens were outgrowing their Cincinanti offices and workshop. They also wanted to get away from the dirty, smokey downtown area. Watches need to be assembled in the cleanest environment possible; in a time when there were still horses on the streets and everyone burned coal, downtown was not the best place for a watch company.

In 1913 the company purchased Nanny Goat Hill, a pasture just outside of Cincinnati, and renamed it Time Hill. Today, this site is on MacMillan Avenue near Interstate 71. The facade is not intended to represent a Swiss chalet, as is commonly thought—instead, Fred was inspired by Medieval guild halls he had seen in Belgium. The building was designed by architect Guy C. Burroughs at a construction cost estimated at $50,000 USD (today this would be about $1.5 million USD). The company moved to the new location in 1917. Fred Gruen had a passion for landscaping, and Time Hill's dramatic hilltop setting was enhanced by carefully planted trees and shrubs, and by a small artificial waterfall that cascaded down the rocks in front. The hill does not look very impressive from MacMillan Avenue, because you can see only the top portion. Actually, MacMillan Avenue is a viaduct; you're not aware of it, but you're actually so high above ground level that another street passes under you, next to Time Hill.

Above: Time Hill, detail from a 1921 ad. This image shows the first phase of construction. Note the figure with knapsack and walking stick climbing the path. The large windows were important, to provide light for the watchmakers inside. After the move, the guild and guild hall became a major theme in Gruen's marketing and advertising, and images of the Time Hill building were used everywhere—on ads, on booklets, on store displays, on watch boxes. Large photos of the building were used in window displays and hung on dealer's walls. Gruen's early steel watch-case alloy was called "Guildite," and Gruen's dealers were "guild members." Many Gruen ads from the 1920s and 30s refer to the company as the "Gruen Guild," although there was never an official name change. Most advertising and marketing materials from the 1920s feature illustrations designed to look like old woodcuts, with scenes of Mediaeval and Renaissance craftsmen. There are often stories about famous watchmakers in the ads, or historical tales about individuals upholding the ideals of their craft. The long-running advertising campaign was very sophisticated for its time—rather than selling individual watch models, the ads attempted to attach an aura of history, craftsmanship and tradition to the Gruen name. Often only a single, small watch was shown near the bottom of the ad, the modern product of Gruen's adherence to the spirit of the old guilds.

Above: Time Hill, from an advertising postcard. This image shows the second of three phases of construction—the front (left in the photo) section of the building has been nearly doubled in width. If you look closely, you can see the seam in the roof where the newer section was added on—the newer section to the left is slightly lighter in color. Note also the hourglass on top of the signpost and the two radio antennae on the roof. Time Hill appeared not only in Gruen's own advertising postcards, but also in postcard sets showing notable Cincinnati landmarks. The guild theme was not simply a marketing ploy. Time Hill was part of an environment the Gruens tried to create, where watchmaking would be practiced as an art and a noble craft. Fred expressed this philosophy in a speech given to a group of business leaders in the 1920s: "It has always been our aim, ever since I started the Guild idea, to foster those ideals of the ancient guilds, of quality and craftsmanship; to make useful things in a beautiful way, under ideal surroundings. We believe in applying art to industry as exemplified in all of our activities, from building a plant whose style of architecture suggests craftsmanship, to making the watches most beautiful, with greatest accuracy obtainable."

Above: By the 1930s, the building had been significantly enlarged. This is an east view from a 1937 advertisement. This photo is taken from exactly the opposite direction from the two views shown previously—the farthest-right section is the rear of the front, which is on the left in the two earlier views. At Time Hill, movements imported from Switzerland were combined with American-made parts to build the finished watches. Solid gold cases, glass crystals and leather straps were made in-house. Gold-filled cases were sometimes manufactured as well, but most of these were contracted out to other firms. In addition to housing these manufacturing operations, Time Hill contained the service shops, company offices and parts warehouse. There was a side entrance where local watchmakers could pick up parts. As mentioned, Gruen sometimes made gold-filled cases at Time Hill, but normally these came from the Wadsworth Case Company, located in Dayton, Kentucky, only a few miles away. These cases often have a tiny Wadsworth "W" logo engraved on the backs, and are signed "Wadsworth" in script inside the case back. A few cases used by Gruen were proprietary Wadsworth designs, and were also used by other companies—an example is the Triad pocket watch case. Wadsworth was one of the more important American watch case companies, making many of the classic cases for Hamilton, Elgin and other U.S. manufacturers. Gruen's platinum and diamond cases came from a facility in New York. Shortly after Time Hill opened, Gruen advertised custom services which included the restoration and refurbishment of older watches. They offered to melt down your old, un-trendy watch case and use the gold to make you a new, fashionable one.

In some early images of the building, various antennae can be seen on the roof. The wireless was still relatively new technology in 1917. Commercial radio broadcasting and even voice communication were still in the future—messages were sent in Morse Code. Time Hill was fitted with one of the most powerful radio transmitter/receivers in the American Midwest, with a sending range of 300 miles and a receiving range of 3000 miles. The wireless enabled the company to receive time signals from the U.S. Naval Observatory in Arlington, Virginia. The ultimate timekeeping reference is astronomical observation, and the Naval Observatory keeps the official time for the United States. Accurate time signals were important to Gruen—one of the major activities at Time Hill was regulating (referred to as "timing") their watches. If the factory's time reference varied, and was slightly fast or slow on any day, the watches adjusted to match the reference would also run slightly fast or slow. The radio provided Gruen with the most accurate time signals available. Shortly before the U.S. entered World War I, Fred sent the U.S. Secretary of War a telegram and letter offering free use of Gruen's powerful wireless station to the government. Pleased with both the building itself and the positive reception it had received, the Gruens decided to build a large, permanent facility to house the Swiss branch of the firm as well. | |

|

c. 1921: The Precision Factory | |

|

Sometime before 1910, the Gruens set up a small factory in Biel, Switzerland. Although several outside firms produced movements, they increasingly manufactured their own from this point onwards. About every year, according to Fred Gruen, the company moved to a larger space. Finally, in 1921 or 1922, Gruen started building a large, very modern factory in Biel. The building's design, which has a family resemblance to Time Hill, was a collaboration between Time Hill architect G.C. Burroughs and a local Swiss architect. Fred had to fight with the local authorities to get the factory built in the style he wanted—the Swiss found the building to be too elaborate and frivolous. However, it became a symbol and a source of pride for the Company just as Time Hill in the U.S. was. Fred felt that the building lent prestige to the company and helped them attract the most skilled workers. From his writing, he was obviously personally quite proud of both buildings.

The Biel factory was also sometimes referred to as Time Hill, but was normally called the Precision Factory or Precision Workshop ("workshop" sounded better in ads about the old guilds). The highest-quality Gruen movements were produced there, and only the watches containing these better calibres were marked "Precision" on the dial and movement. For many years, less-expensive movements were still purchased from outside firms, but by the late 1930s all Gruen movement production was consolidated at the Precision Factory.

Above: The Gruen Precision Factory in Biel/Berne, Switzerland, in a photo from the 1929 Gruen Dealers' catalog. Note the "Precision" logo above the bottom two windows on the far left of the building. In German, Gruen means "green." The company made a point of using green tile for the roofs of both Time Hill and the Precision factory, and Fred Gruen used green tile on the roof of his own house. Continuing with the company's interested in the wireless, Time Hill established regular two-way radio communications with the Swiss facility. The early 1920s were a very productive time for Gruen, and their new Swiss factory was busy from the start. The watch market in the United States was booming. In contrast, much of the rest of the Swiss watch industry was in serious trouble. The effects of the First World War had devastated the national economies in most of Europe and Asia. The United States had its own flourishing watch industry—Gruen, Hamilton, Bulova, Elgin, Waltham, Illinois and others supplied the middle and high end of the market, while cheap Swiss imports supplied much of the bottom end, along with American companies like Ingersoll. More expensive Swiss watches made up only a small percentage of U.S. sales. This left many of the better Swiss companies with no place to sell their watches; some had to cut their work forces by as much as half, leaving many skilled workers unemployed. Seeking cheaper watches, many distributors farmed out production to termineurs, small Swiss sweatshops which produced very cheap watch movements from mass-produced parts. This took still more work away from the larger Swiss companies. Fred Gruen campaigned to have U.S. import laws changed, since they offered tax incentives to these cheaper watches and penalized better quality ones. Since many highly-skilled watchmakers were unemployed in Germany and Switzerland, Gruen hired some of the best ones and brought them to America. Fred, who had learned to design and build watch movements from scratch at the Royal Horological Institute at Glashütte, tested for similar skills and abilities in the candidates for these jobs. He supplied specifications and materials, from which a new watch movement had to be designed and constructed. This required the ability to plan the layout and compute the correct gear ratios for the various wheels, and the physical skills needed to machine, fit and finish the parts. If this task was completed to Fred's satisfaction, the candidate would be given transport to the U.S. and set up as a Gruen employee. An elite group of these German-speaking watchmakers worked upstairs at Time Hill.

Up until at least the late 1920s, all Gruen pocket watches with Precision movements came with a beautiful, full-color certificate printed on parchment. The certificate includes a guarantee that the watch will perform to current railroad accuracy standards. After the sale, the purchase information was recorded by the dealer who then sent the certificate to Time Hill, where Fred Gruen personally signed and returned it. The company kept meticulous records of customers and individual watches. Unfortunately, almost all of the Gruen Company's paperwork has been lost or destroyed.

[ 1867 | 1894 | 1904 | 1917 | 1921 | 1922 | 1929 | 1940 ] [ Contents | Intro | Sources | Links | FAQ | Patent | Cover ]

Copyright © 1999-2001 Paul Schliesser

contact

|

|

Right: This fanciful illustration from a 1920s ad shows the symbolic image of Renaissance craftsmen going to work at Time Hill. All of Gruen's advertising and marketing from this time period emphasized the guild theme.

Right: This fanciful illustration from a 1920s ad shows the symbolic image of Renaissance craftsmen going to work at Time Hill. All of Gruen's advertising and marketing from this time period emphasized the guild theme.

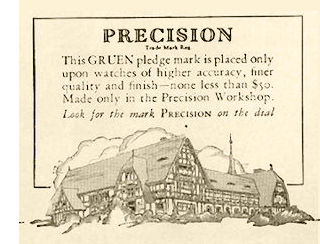

Right: Detail from a 1929 ad. Gruen took the "Precision" marking very seriously—this was an indication of their best-quality watches. Although the picture shows Time Hill in Cincinnati, all Precision movements made after 1921 came from the Precision Factory. The starting price of $50 for the least-expensive Precision watch would be the equivalent of about $1275 today.

Right: Detail from a 1929 ad. Gruen took the "Precision" marking very seriously—this was an indication of their best-quality watches. Although the picture shows Time Hill in Cincinnati, all Precision movements made after 1921 came from the Precision Factory. The starting price of $50 for the least-expensive Precision watch would be the equivalent of about $1275 today.