|

1867: One word from a woman's lips |

|

Although the Gruen Watch Company was founded in 1894, the company later traced its history back to 1874, following the early career of its founder.

Dietrich Gruen (originally spelled 'Grün') was born in Osthofen, Germany in 1847. After attending both public and private schools, at age 15 he was sent away from home to learn the watchmaking trade. He was an apprentice to a watchmaker named Martens in Friedburg, Germany, and also worked in the towns of Carlsruhe, Wiesbaden and Lode. In 1867 he traveled to the U.S. following his three brothers, who had immigrated several years earlier. One brother had been killed in 1863, in the American Civil War. During his visit, Dietrich met and fell in love with Pauline Wittlinger, a schoolteacher and the daughter of a Delaware, Ohio watchmaker. After working as a watchmaker in St. Louis, Cincinnati and Columbus, Dietrich married Pauline in 1869, moved to Delaware, Ohio, and went to work for her father. Years later, a Gruen advertisement told how “one word from a woman's lip” (Pauline’s “yes” to Dietrich’s marriage proposal) changed horological history. Dietrich and Pauline's first son, Frederick G. Gruen, was born in 1872. Fred was to become an important figure in the Gruen story. |

|

|

1874: The Safety Pinion |

|

| On June 12, 1874, Dietrich applied for a patent on an improved safety pinion, which was granted on December 22. He was 27 years old. Because this was his first important contribution to horology, in the future the Gruen Watch Company would take 1874 as its founding date.

In later years, alloys for unbreakable mainsprings were developed, but the large and powerful mainsprings used in older pocket watches tended to be brittle and commonly broke. The recoil, caused by the sudden release of the energy stored in the spring, could strip teeth off of wheels and snap pivots, doing tremendous damage to the movement. The safety pinion, mounted on the shaft which also holds the center wheel, is the interface between the potentially destructive power in the mainspring and the fragile moving parts in the rest of the watch. Dietrich's invention consisted of a simple device which, in the event of mainspring breakage, uncoupled the pinion and allowed it to spin freely without passing the dangerous shock through the shaft to the center wheel and the rest of the mechanism. The pinion itself would not be injured and did not need to be replaced. In his patent application, Dietrich gave his address as Delaware, Ohio, an indication that he was not yet making watches in Columbus. |

|

|

1876: The Columbus Watch Manufacturing Company |

|

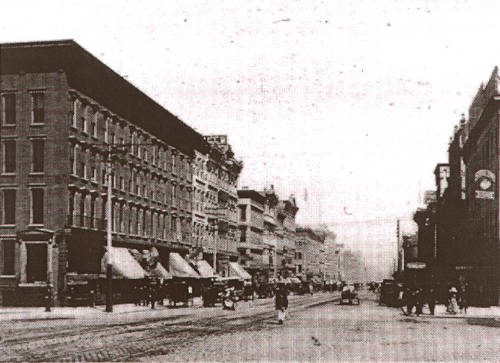

Above: A view of the corner of Broad and High Streets in Columbus, probably taken in the early 1880s. The Columbus Watch Manufacturing Company was located in the large building on the left, called the 'Deshler Block,' at 1 North High Street. The comapny moved here in 1878 or 1879. There is a large sign in the shape of a pocket watch hanging between the first and second awnings. This building was diagonally across the street from the Ohio state capitol building; this photo was taken near the corner of the capitol's lawn. Today, there is a small historical plaque marking the former location of the Deshler Block. (Image courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.) Dietrich started the Columbus Watch Manufacturing Company in 1876. The first offices were at 117 1/2 High Street in Columbus. Deitrich was President, and William J. Savage was Secretary and Treasurer. Although 1874 was used later by the Gruen Watch Company as a founding date, and is the date given in nearly all recent histories, I don't believe that this is correct. Articles, books and jewelers' newsletters from the 1800s all give 1876 as the founding date. The Gruen Watch Company itself used 1876 in advertising until about 1915. Savage was the elder son of William M. Savage, one of Columbus’ most prominent citizens and most successful businessmen. (Note that William M. is the father and William J. is the son — several 1800s publications confuse the two names.) A watchmaker and gunsmith, the 1874 Columbus street directory lists the father’s trade as, ‘watches, jewelry, guns, revolvers and fishing tackle.’ Prior to 1875, William J. Savage was involved in the wholesale jewelry trade and also seems to have been trained as a silversmith. Savage sold his share of his father’s business in order to raise capital to invest in the watch company. The financial security his partner provided allowed Dietrich to concentrate on supervising the factory, coordinating production in Switzerland, and selling. Right: In his Columbus workshop, Dietrich modified, finished and cased imported raw movements manufactured by Leo Asbey in Switzerland. These new watches included his patented safety pinion. The size and wearing comfort of a pocket watch was always a concern of his, so Dietrich introduced 16-size watches as an alternative to the heavy and thick 18-size and larger watches that were prevalent at the time. It is also claimed that he introduced the first stemwind watches sold in the U.S. market. A second son, George J. Gruen, was born in 1877. In about 1878 or 79 the company moved to the Deshler Block, diagonally across the street from the Ohio capitol building. I had previously believed that this was the original location, (and all other histories that I have seen claim this). Dietrich’s son Fred later wrote that the company started here, but the 1870s Columbus street directories tell a different story. Instead, this is probably the first location that Fred, who was about six years old at the time, clearly remembered. Output during this time was about 10 watches per day. Sometime before 1882, the company moved to two floors in a commercial building a few blocks away. Fred Gruen described a home-made phone system using catgut to allow communication between floors. Very little information exists for the early years of the company. The tables of dates and serial numbers used in collectors' guidebooks and price lists are educated guesses, but are skewed because they start two years too early. |

|

|

1882: The Columbus Watch Company |

|

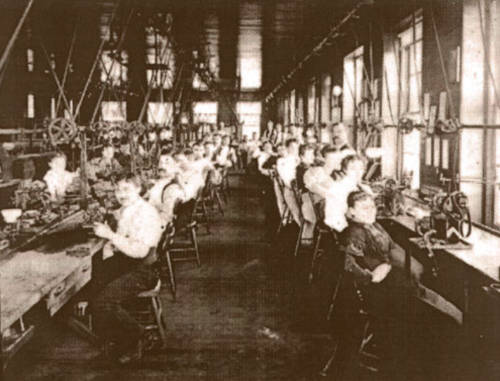

Above: Interior of the Columbus Watch Company's Thurman Street factory, date unknown. Complete watch movements were designed and manufactured in this new facility. (Image courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.) Under Gruen and Savage the Columbus Watch Manufacturing Company was small but very successful, and began to attract the interest of bankers and investors. In 1882, in collaboration with a number of new partners, the company was reorganized as the Columbus Watch Company and moved to a newly-constructed factory building located on Thurman Street, in the 'German Village' section of Columbus. Dietrich was President of the new corporation. The building was tall and narrow, with very large windows, to provide adequate light for the delicate work of building watches.

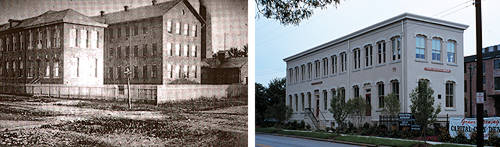

Above, left: Photo of the Columbus Watch Company building from 1889. The front building, on the left, is the original structure completed in 1882. In the rear, the small, dark brick building with the tall chimney housed a steam engine, which supplied power to the factory machinery via belts and pulleys (as seen in the interior photo). From the pattern of windows, it seems that the interior photo was taken in the larger, middle building. The two front buildings were connected, forming an 'H' shape. (Courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.) Above, right: The original 1882 building, photographed in September 2000. This oldest section of the factory, now an office building, is the only portion still standing today. The current tenants are a large dentist's office and an advertising agency. Joining the ranks of older established American watch companies like Waltham and Elgin, the new company designed and manufactured their own in-house movements, instead of finishing imported ones as Gruen had done previously.

By 1888 production was about 45 watches per day; the company would grow to 300 employees and output increased to 150 watches per day. Although the company continued to issue stemwind watches, they also manufactured keywind movements for some of their less-expensive models. Starting when Fred was very young, Dietrich involved his older son in the business. During breaks from school Fred worked in the engine room, blacksmith and machine shops, and was later given more skilled jobs in the gilding and die departments. After earning a mechanical engineering degree at the University of Cincinnati, Fred was sent to Germany to study at one of the most respected European watchmaking schools, graduating with top honors from the Horological Institute of Glashütte in 1893. During his studies, he designed and built both a chronograph and a repeater movement, according to small notices in an 1890s Jeweler's publication. Fred quickly became an important part of the company. Shortly after returning from his studies, he began to streamline and reorganize manufacturing processes at the Columbus Watch Company, starting with the jewelling department, which up until then had been a bottleneck in the production of finished watches.

Things had gone very smoothly for the young company, but this was not to last. The Panic of 1893 was devastating to the U.S. watch industry. This was one of the worst economic periods in American history, second only to the Great Depression, and lasted for several years. (What we now would call ‘depressions’ were once referred to as ‘panics’. In the early 1930s, President Herbert Hoover coined the term ‘depression’ to put a cheerful spin on the harsh economic conditions that his administration was being blamed for—the U.S. was not experiencing a panic, merely an economic depression. This term has stuck.) American watch companies were forced to reduce prices and cut wages, and several did not survive. During this same time, Waltham and Elgin engaged in a vicious price war which hit the Columbus Watch Company very hard. Fred later wrote that he believed his father’s company was specifically targeted by these powerful rivals. The smaller and younger company did not have the financial resources to weather the crisis.

After a series of disagreements with the other partners, Dietrich and Fred left the Columbus Watch Company in 1894, shortly before the business went bankrupt. Dietrich had lost his share of the company to the investors, and was faced with the prospect of staying on as a salaried employee at the company that he had founded. He chose to leave rather than bear this indignity. After the departure of the Gruens the firm was reorganized, refinanced and renamed "The New Columbus Watch Company." For collectors wishing to know if a Columbus watch is from the Gruen era: The Complete Price Guide to Watches indicates that the Gruens would have left around serial number 229,000. (As mentioned earlier, I question the accuracy of existing Columbus serial number lists, but I believe that later numbers are more credible than early ones.) After 1894, Columbus watches started to have names like Time King and Railway King. The pre-1894 models were not named. Although after 1894 the official name was The New Columbus Watch Company, many dial and movement markings still used the original name, most likely to use up existing parts that were already marked. The New Columbus Watch Company survived until 1903. The contents of the factory, including all the tooling and stocks of movements, were eventually purchased by the Studebaker family, moved to Indiana (along with many key employees) and used to start the South Bend Watch Company. Some early South Bend watches were sold with signed Columbus movements in them.

[ 1867 | 1894 | 1904 | 1917 | 1921 | 1922 | 1929 | 1940 ] [ Contents | Intro | Sources | Links | FAQ | Patent | Cover ]

Copyright © 1999-2001 Paul Schliesser

contact

|

|

Right:

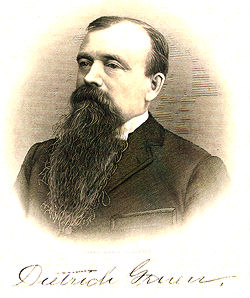

Dietrich Gruen (1847-1911), founder of the Columbus Watch Company and co-founder (with his oldest son) of the Gruen Watch Company; this engraving was printed in 1891. (Image courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

Right:

Dietrich Gruen (1847-1911), founder of the Columbus Watch Company and co-founder (with his oldest son) of the Gruen Watch Company; this engraving was printed in 1891. (Image courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

Right: A detail from Dietrich's 1874 safety pinion patent drawings. See the

Right: A detail from Dietrich's 1874 safety pinion patent drawings. See the  16-size, stemwind, lever-set Columbus pocket watch, with a 14k yellow gold case, 1870s. The serial number, 4277, means it was made during the first few years of production. Note the logo on the dial, which is a stylized ‘C W Co.’ for ‘Columbus Watch Company.’ The logo, numbers and all other dial markings would have been painted by hand, using a finely-pointed brush.

16-size, stemwind, lever-set Columbus pocket watch, with a 14k yellow gold case, 1870s. The serial number, 4277, means it was made during the first few years of production. Note the logo on the dial, which is a stylized ‘C W Co.’ for ‘Columbus Watch Company.’ The logo, numbers and all other dial markings would have been painted by hand, using a finely-pointed brush.

Left: William F. Sauer, foreman of the Columbus Watch Company until 1890. In what seems a strange series of career changes, he became an agent for the Schlitz Brewing company, and in 1899 opened his own cafe. (Courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

Left: William F. Sauer, foreman of the Columbus Watch Company until 1890. In what seems a strange series of career changes, he became an agent for the Schlitz Brewing company, and in 1899 opened his own cafe. (Courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

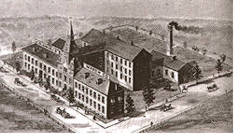

Left: The Columbus Watch Company as shown in an 1888 issue of the Columbus Dispatch. I do not believe the tower or the enlargements to the front section were ever actually built—the building as it stands today shows no trace of them. (Courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

Left: The Columbus Watch Company as shown in an 1888 issue of the Columbus Dispatch. I do not believe the tower or the enlargements to the front section were ever actually built—the building as it stands today shows no trace of them. (Courtesy of the Columbus Metropolitan Library.)

Left: Columbus 18-size pocket watch, circa 1893.

Left: Columbus 18-size pocket watch, circa 1893.