|

1894: D. Gruen & Son | |

|

After leaving the Columbus Watch Company, Fred found a job with a large company in Cincinnati, Ohio, working at a watchmaker's bench in a basement, sitting next to noisy machinery. Unhappy with his working conditions and his prospects, he took the train to Columbus and met with his father at the train station. They had a long talk and decided to start a new watch company. Right: Using money borrowed from friends and relatives, Dietrich and Fred formed the partnership D. Gruen and Son. Together they began to design a completely new 18-size movement. Since Fred had studied in Germany, the watch was designed in the Glashütte style, but incorporated innovations by the Gruens. Because of the economic situation in the U.S., Fred traveled to Germany and arranged to have the movements manufactured by Assmann in Glashütte. This was a highly respected watchmaking firm, originally started by Julius Assmann in 1852 with help from Adolf Lange (founder of A. Lange & Söhne). The Assmann firm was particularly known for the beautiful finishing of watch movements. Part of the agreement Fred reached required him to remain in Germany for a year, helping Paul Assmann modernize the factory along American lines. At this time, most German watchmaking was done in facilities that were closer to cottage workshops than to factories. Among other tasks, Fred produced engineering drawings for new jeweling machines and supervised production of the new Gruen movements. In addition to the watches manufactured by Assmann, the Gruens sold a beautiful repeater model with a LeCoultre movement.

These first Gruen watches are of very high quality and are beautifully made. Both 18 and 16 size versions were manufactured, each in both open face and hunter styles, and in 18- and 21-jewel versions. The 18-jewel models had an extra cap jewel on the escape wheel to make removal of the escapement easier.

Above and below: A 16-size D. Gruen and Sons hunter-case model. The highly-polished movements are gorgeous.

Once production was underway and Fred had returned to the United States, he and his father handled sales, with occasional help from Fred's younger brother George. Fred claims that he spent 9 or 10 months per year on the road doing sales trips. The Gruens dealt directly with individual jewelry stores; there were no wholesalers or jobbers involved in the distribution of their watches. | |

|

1898: Moving to Cincinnati | |

|

George Gruen, Dietrich's second son, went to business school instead of being trained as a watchmaker.

After working for a time in accounting jobs, he joined his father and brother in about 1898 as treasurer and financial officer. The company name was changed to D. Gruen and Sons, then to D. Gruen, Sons & Company when the firm was incorporated. Because of the continuing economic crisis, George's job was difficult and he often had trouble coming up with enough money to pay the company's bills. However, the persistence of the Gruens paid off, and within a few years conditions had improved. The watches were selling well, and the small firm was building strong relationships with dealers. In 1898 the company was relocated from Columbus to Cincinnati, occupying space in the Johnson Building on Fountain Square, in the heart of the downtown area. The same year, the Gruens purchased the Queen City Watch Case Company and changed its name to the Gruen National Watch Case Company. Although run by the Gruens, it was kept as a separate company.

Around 1900, the Gruens decided to take some movement production out of Germany. Many of the skilled workers in Glashütte were unwilling to embrace changes to their traditional manufacturing methods, and resented the fact that these changes were being brought in by an outsider, so Fred was forced to hire new employees and train them. There may also have been economic considerations involved in the shift. The Gruens would eventually take all their business to Switzerland, where the trend towards American-style mass production was greeted with more interest and enthusiasm. Watches manufactured using German movements were signed “D. Gruen and Sons”. For a few years after the changeover to Swiss calibres, dials and movements were signed with a stylized “DG&S” logo. Starting about 1910 the watches were simply marked “Gruen”. | |

|

1904: The VeriThin "the most beautiful watch in America" | |

|

Dietrich seems to have always been concerned with the size and wearing comfort of pocket watches. By the early 1900s, most Gruen watches had shrunk from 18- to 16- to 12-size. Having made the watches smaller, the next goal was to make them thinner.

Normally, a watch movement has wheels and other parts overlapping on four different levels. In the VeriThin movement, by making changes to the traditional layout, it was possible to reduce this to three levels, allowing the watch to be made much thinner.

The Gruen-designed movements were manufactured in Switzerland. For the rest of their history, Gruen would continue to build movements there, and case and time them in the U.S. Gruen's new VeriThin was between 10- and 12-size and only about 7mm thick; this was a reduction of almost one-third compared to a normal 12-size watch. These were originally seen as novelties, and the first batches had technical problems, but the VeriThins eventually became Gruen's most popular models, and helped steer the whole industry away from the large sizes that were still common at the time. These small, thin watches were very comfortable to carry in the vest pocket, especially in comparison to a thick and heavy 18-size watch, and after the initial teething problems proved to be very reliable. Models with Precision movements were guaranteed to meet railroad accuracy standards. To understand the place in the market Gruen carved out for itself, it is important to understand how important railroad watches were in the U.S. in the 1890s and early 1900s.

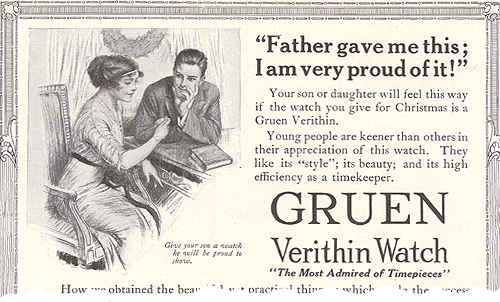

Above: A portion of a 1913 ad. Old Gruen marketing materials often give a vivid glimpse of the era in which the watches were made. There was no way to communicate with it once a train had left the station—often, knowing whether another train was speeding towards your train in the opposite direction depended on both engineers knowing the exact time and keeping precisely to their schedules. This made accurate watches a matter of life and death. The tragic incident that led to the adoption of railroad standards for watches was a head-on collision between a passenger train and a high-speed freight train, which resulted in the deaths of the train crews and many passengers. Investigators blamed the crash on a four-minute error on one engineer's watch. The United States was to lead the world in the production of high-quality (and very expensive) railroad watches; before the 1930s many imported Swiss watches were merely cheap imitations of American watches.

The "railroad watches" used by engineers, conductors and other railroad employees were required to be accurate to plus-or-minus 30 seconds per week, in addition to meeting a number of physical and technical requirements. Railroad employees had to buy their own watches, from a list of approved models. There were payroll deduction plans to help with the purchase, since the cost might represent two month's salary or more. Railroad inspectors serviced and adjusted these timepieces regularly, and records were kept for each individual watch. American railroad pocket watches were among the most precise small timekeeping devices in existence at the time. Many of the other U.S. companies were concentrating on railroad watches at this time; the larger railroads needed thousands of them, and the same watches were also offered to the public, who were assured of getting a superlatively accurate timepiece by purchasing a railroad-approved model. However, U.S. regulations stipulated that railroad watch movements be American-made, closing this lucrative market to the Gruens, even though their watches could meet all of the technical and accuracy requirements of railroad service. However, they were able to sell railroad watches in Canada, and these can be found with both German and Swiss Gruen movements in them.

Offering watches that were approved for railroad service was a guarantee that a manufacturer's watches could pass the most stringent quality requirements of the era; this lent the manufacturer great prestige in the marketplace, and companies like Hamilton (whose "The Watch of Railroad Accuracy" banner graced Hamilton's ads until the 1950s) made much of this. This marketing advantage was denied to Gruen. Their strategy was to offer elegant, thin, dress watches instead of trying to compete with the large and heavy railroad models, yet they guaranteed the same accuracy as the much bulkier watches.

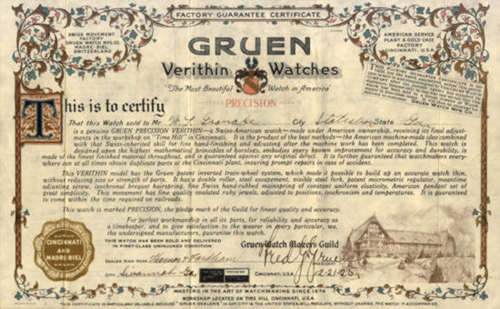

Above: The certificate sent to owners who registered a VeriThin watch with Gruen; this one is from 1926. Note that these were individually signed by Fred Gruen. The certificate states that if the watch fails to perform to railroad accuracy standards, any Gruen dealer will regulate it free of charge. Unlike most other watches at the time, Gruen's pocket watches were always sold as complete, cased watches, in a presentation box. Most other firms sold only the movement, with hands and dial attached; these came in a small metal can with a paper label pasted on the top. When a customer shopped for a watch, he picked a dial/movement then picked a case that would fit it, and the jeweler combined them to build a complete watch. Some watch companies also offered a line of cases, but most did not sell these together as a finished watch. Because movements and cases came in standard sizes, they were (and still are) easily interchangeable. If a watch case started to look worn or became unfashionable, you didn't buy a whole new watch, you just replaced the case; if the watch movement was irreparably damaged or worn out, you'd have a new one installed in your existing case. There were hundreds of watch case companies to meet the demand. The customer could also spread out the cost of an expensive watch by purchasing a good movement and housing it in a cheap case until he could afford a better one. Vintage watch dealers are still swapping these cases and movements around today, so if you're concerned about historical accuracy you should look carefully at each combination. Gruen's method of selling complete watches assured that the movement had been regulated in its actual case, and did not need to be tampered with by a third party who might upset the delicate adjustments. The VeriThin movements are an odd size (they are between 10- and 12-size), in addition to being thin, and will not fit standard-size watch cases.

Also unlike most other companies, Gruen watches were sold directly to Gruen dealers, as was mentioned above. There were no middlemen, distributors or wholesalers between Gruen and the local jewelry store. The company would eventually have a large sales force, and by the 1930s they would have around 1200 dealers. Because Gruen dealt directly with dealers, without intermediaries, they were able to stay in touch with what their dealers, and the public, wanted. Fred Gruen claims to have introduced the use of applied numbers and markers on watch dials. In the 1800s and early 1900s, watch dials were enamel with painted markings. After looking at very old clocks and watches in European museums, Fred decided to do some metallic dials with gold applied numerals. The firm that Gruen contracted to make these dials initially resisted the idea, but they quickly became very popular and were soon copied by other manufacturers. From the 1930s through the 1960s, almost every watch manufacturer in the world used a metal dial with applied figures on at least some of their watches. Although he had taken out many patents on behalf of the company, Fred later regretted not having taken out a patent on applied dial figures.

[ 1867 | 1894 | 1904 | 1917 | 1921 | 1922 | 1929 | 1940 ] [ Contents | Intro | Sources | Links | FAQ | Patent | Cover ]

Copyright © 1999-2001 Paul Schliesser contact

|

|

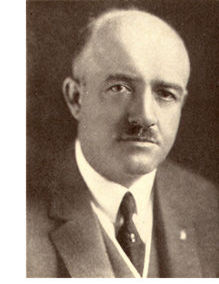

Dietrich's oldest son, Frederick Gustavuus Gruen (1872-1945). This is his official portrait used in Gruen marketing materials from the 1920s. He was affectionately referred to as “Mr. Fred” by Gruen employees.

Dietrich's oldest son, Frederick Gustavuus Gruen (1872-1945). This is his official portrait used in Gruen marketing materials from the 1920s. He was affectionately referred to as “Mr. Fred” by Gruen employees.

Left: The earliest-known D. Gruen & Son movement, circa 1894. Serial numbers started around 62000. This example is 18-size with 21-jewels. It features a gold poised pallet and gold escape wheel. The finishing by Assmann includes gold-filled engraving and various forms of surface decoration and damaskeening; the winding wheels show the traditional Glashütte "solar" pattern. (Thanks to Jack Goldberg for this photo.)

Left: The earliest-known D. Gruen & Son movement, circa 1894. Serial numbers started around 62000. This example is 18-size with 21-jewels. It features a gold poised pallet and gold escape wheel. The finishing by Assmann includes gold-filled engraving and various forms of surface decoration and damaskeening; the winding wheels show the traditional Glashütte "solar" pattern. (Thanks to Jack Goldberg for this photo.)

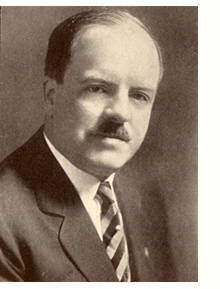

Left: George John Gruen (1877-1952) brought his business and accounting skills to the new company. This photo is from the 1920s.

Left: George John Gruen (1877-1952) brought his business and accounting skills to the new company. This photo is from the 1920s.

Right: 17-jewel D. Gruen and Sons 12-size pocket watch, early 1900s. Just as with the "C.W. Co." marking on early Columbus watches, if you didn't know the logo is "D.G. & S." for "D. Gruen and Sons," you wouldn't know you had a Gruen watch. This logo was used for a time after production was moved to Switzerland, and is sometimes seen on movements even when the dial is marked "Gruen."

Right: 17-jewel D. Gruen and Sons 12-size pocket watch, early 1900s. Just as with the "C.W. Co." marking on early Columbus watches, if you didn't know the logo is "D.G. & S." for "D. Gruen and Sons," you wouldn't know you had a Gruen watch. This logo was used for a time after production was moved to Switzerland, and is sometimes seen on movements even when the dial is marked "Gruen."

Right: Detail from a 1923 ad illustrating the VeriThin concept. The solid black area represents the thickness of the watch movement. Attempts to build such thin movements had been made before, but Gruen's was the first that was technically and commercially successful.

Right: Detail from a 1923 ad illustrating the VeriThin concept. The solid black area represents the thickness of the watch movement. Attempts to build such thin movements had been made before, but Gruen's was the first that was technically and commercially successful.

Left: This watch, and a few that I've seens similar to it, are a mystery to me. Because of the hand-painted, porcelain dial I assume that this is a very early VeriThin, but this is only a guess. The movement is different from the usual models. A 1911 Gruen invoice at the NAWCC Research Library shows a Verithin logo similar to this one, but the watches shown in ads from 1911 onwards do not show dials signed like this. I'd welcome new information about these.

Left: This watch, and a few that I've seens similar to it, are a mystery to me. Because of the hand-painted, porcelain dial I assume that this is a very early VeriThin, but this is only a guess. The movement is different from the usual models. A 1911 Gruen invoice at the NAWCC Research Library shows a Verithin logo similar to this one, but the watches shown in ads from 1911 onwards do not show dials signed like this. I'd welcome new information about these.

Left: A VeriThin from the 1910s. This watch has a 17-jewel non-Precision movement. The original customer could choose a movement from one of three grades, marked (in order of increasing quality) Gruen Guild, Precision or Extra-Precision. Even the regular Guild movements were of excellent quality, and the two Precision grades were of extremely high quality. Initially some Precision movements had 15 jewels (men's pocket watches with as few as seven jewels were common from other manufacturers) but Gruen quickly decided that 17 jewels minimum were required for their Precision watches, and later even the lower grades got an increase from 15 to 17 jewels.

Left: A VeriThin from the 1910s. This watch has a 17-jewel non-Precision movement. The original customer could choose a movement from one of three grades, marked (in order of increasing quality) Gruen Guild, Precision or Extra-Precision. Even the regular Guild movements were of excellent quality, and the two Precision grades were of extremely high quality. Initially some Precision movements had 15 jewels (men's pocket watches with as few as seven jewels were common from other manufacturers) but Gruen quickly decided that 17 jewels minimum were required for their Precision watches, and later even the lower grades got an increase from 15 to 17 jewels.

Right: A VeriThin with a 19-jewel V2 1/2 Precision movement; late 1920s. The dial engraving is quite beautiful.

Right: A VeriThin with a 19-jewel V2 1/2 Precision movement; late 1920s. The dial engraving is quite beautiful.