|

VeriThin, SemiThin, Very-VeriThin, UltraThin, Ultra-VeriThin | |

|

Above: A comparison of pocket watch sizes and thicknesses. Top right: 1880s Columbus 18-size watch, typical of the time; middle left, early-1900s DG&S 12-size; bottom left (with blue dial numbers): early VeriThin; bottom right: Dietrich Gruen UltraThin. The VeriThin pocket watches were popular and became Gruen's signature watch. Prices for these models started at $50 USD (which would be roughly $1250 USD today). Adding the best Precision movement and a precious-metal case could take the price up to several hundred dollars. Some of the old, thicker movements were kept in production and became the SemiThin pocket watch line, priced in the $25-35 USD ($625-$875 USD) range. These were not offered in Gruen's Precision grade. Interestingly, many of the SemiThin models have very ornate cases and dials, while many of the more expensive VeriThin models are very plain. Gruen was one of the most expensive and prestigious watch brands available in America. A SemiThin might cost only $25 USD, but this was still not cheap. Truly inexpensive watches were from companies like Ingersoll, and sold for as little as $1 USD.

Very-VeriThin models combined ordinary VeriThin movements with extra-slim case designs that made the watches look even thinner. The very expensive UltraThin, movement, building on the VeriThin concept, managed to reduce the number of operating levels in the movement to two. These watches are impressively thin; practical considerations, such as the structural rigidity of the case, would preclude a watch much thinner than this, even if an appropriate movement could be developed. The UltraThin models were part of the pricey Dietrich Gruen line, which will be described later. The cost of an UltraThin, as shown in the 1929 catalog, ranged from $375 USD for a model in an 18k gold case up to $1250 USD for a platinum-and-diamond cased model (

Above: a Dietrich Gruen UltraThin with a solid gold case. The Ultra-VeriThin was a less-expensive alternative to the UltraThin, occupying a niche between the UltraThin and the regular VeriThin. The Ultra-VeriThin watches were Precision grade; prices started around $100 USD (about $2500 USD today). Like other models, adding a precious-metal case could make the price substantially higher.

Above: A detail from a 1923 ad comparing the SemiThin, VeriThin and Ultra-VeriThin concepts. Gruen's thin watches soon prompted their competitors to offer thinner and smaller watches as well. With the exception of railroad watches, which by regulation had to be 16-size or larger, the trend in the industry moved towards the smaller sizes. Gruen's Precision models were guaranteed to meet railroad accuracy standards, so there was no advantage to carrying a chunky 18-size watch in your vest pocket all day. | |

|

1908: Wristwatches | |

|

Gruen made both men's and women's wristwatches starting in 1908, but these proved popular only with women. Gruen was one of a very few companies to take wristwatches seriously this early, seeing their potential in spite of disappointing early sales to male customers.

Above: A convertable watch attached to a neck chain. This watch has beautiful blue enamel decoration on its gold case. Below: A convertible watch attached to a silk ribbon so it can be worn on the wrist. Convertible watches allowed a woman to own a single watch that could be worn in different ways.

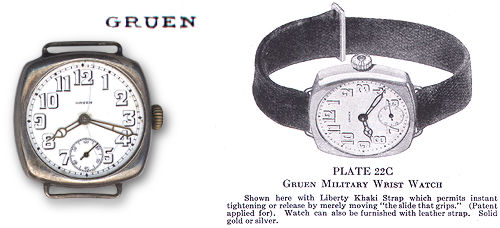

One design that was popular with women was the convertible watch. These were shaped like a very small pocket watch. In addition to the bow on the top (the metal ring or loop that allowed it to be attached to a chain), these included a second, small ring on the bottom, to allow attachments at both ends. Included was a bracelet or ribbon that clipped to the top and bottom of the watch to form a wristwatch, but the watch could also be worn on a neck chain, could be pinned to the clothing or used with a pocket watch chain. Because these small watches were so expensive, the design allowed a woman to own one watch that could be worn in different ways. The tiny movements from watches like this were also used in the first men's wristwatches, since they were the smallest watch movements available at the time. Left: Gruen also made true wristwatches (women's models were usually called "wristlet watches") with a bracelet permanently attached. Most men saw wristwatches as being extremely effeminate and continued to carry pocket watches. Things began to change after the military on both sides used wristwatches during the First World War. When huddled in a muddy trench or flying an airplane, a wristwatch proved to be much more practical and convenient than a pocket watch, and was easier to protect from damage. This helped to remove the wristwatch's feminine stigma, making them acceptable for men to wear in civilian life. However, most manufacturers, including Gruen, were careful to call them "strap watches" since "wristwatch" still sounded effeminate to male customers. Right: Gruen made both wrist and pocket watches for the military during World War I. Most had silver cases, which would tarnish but would not corrode under adverse conditions. To satisfy U.S. military regulations, these watches all have luminous dial markings and hands. The luminous material used at the time contained radium, and was painted onto the dials by hand. The dangers of using such a potent radioactive material were not understood at the time, and appropriate precautions were not taken. This had tragic consequences for many dial painters (who were mostly women). Watches from the 1950s onwards use the mildly-radioactive element tritium instead of radium, and today many watches use new materials that are not radioactive at all.

Above: A World War I-era Gruen military-style wristwatch. The 32mm case is solid silver, and is surprisingly heavy. The back snaps on, unlike the round man's wristwatch shown previously. The dial is porcelain; the hands and numbers would originally have been luminous. The 15-jewel movement is signed both "DG&S" and "Watch Specialties Company." Watch Specialties was a Gruen subsidiary that imported non-Gruen movements during the 1910s. To the right is a detail from Gruen's 1918 book, A Worthy Company of Watchmakers, showing this watch with the company's "Liberty" strap. A metal "shrapnel guard" was available which protected the glass; a pattern of holes allowed the time to be read with the guard in place. After the War, watches identical to the one shown were sold until about 1922 as sports or outdoor watches. Gruen also made a military version of the VeriThin pocket watch, which had a luminous dial and hands as the military wristwatches did. These came in either solid gold or gold-filled cases. Gruen's 1918 book, A Worthy Company of Watchmakers suggested that officers needed to carry two watches; a pocket watch for accuracy and a wristwatch for convenience. Later in the 1920s, the company would offer the same advice to civilians.

Above: "Moisture Proof Military Wrist Watch—Gruen Patent," from the 1918 book. The actual watch is hinged inside an outer case with a screw-on bezel and crystal. The watch is completely sealed inside the outer case, so the bezel must be unscrewed to get access to the watch to wind and set it. The angled rim of the bezel is milled to enable the owner to get a secure grip when loosening or tightening it. The milled bezels on some modern wristwatches (many Rolex models have these) are purely decorative elements based on this originally functional detail. In the early 1920s, this model (in your choice of solid silver or solid gold case) was sold to sportsmen as a "Rough N' Ready, Out O' Doors" watch.

| |

|

1911: The Dietrich Gruen watches "nothing finer known to the watchmaker's art" | |

Right: Dietrich Gruen's best-known portrait.

Dietrich Gruen's best-known portrait.

Dietrich died suddenly in 1911, while he and Fred were nearing the Italian coast on board the steamship Berlin. Fred was on one of his frequent business trips to Europe. His father had been suffering from a heart ailment since 1905, and was en route to a spa at Bad Nauheim, Germany, which he visited annually for treatments. Fred, who succeeded Dietrich as President, later wrote that stress was the cause of his father's death. The years since leaving the Columbus Watch Company had often been difficult, and Dietrich had refused to "take it easy" in spite of his heart problems and his doctor's orders. "He was a lovable character," Fred wrote about his father, "a hard worker who knew his business, a square shooter, a man you could trust and fine to work with, and I will give him credit for giving George and me full swing and authority in the business. He used to say, 'I would rather have you make some mistakes as long as you don't repeat them, than not have responsibility and always be afraid to make a decision.' I am awfully glad he did that, for it gave us the opportunity to develop the ability to make our own decisions and make them quickly. If it had not been for that, we would never have gotten where we did." A series of new, thinner pocket watch movements had been under development, which Dietrich did not live to see put into production. In his memory, this new line of watches did not have the normal Gruen logo, but were simply signed "Dietrich Gruen" in script on the dial. These were Gruen's finest watches at the time, and were thin, elegant, and expensive. Until the advent of the 50th Anniversary watch, these were Gruen's most prestigious models.

A 1917 ad reads, "Planned by Dietrich Gruen himself as his last work, and carried to completion by his sons and associates, this watch sets a new standard in watch construction and finish, and is in every respect worthy of the name of this Master of Watch Craftsmanship." The original line had three models: one with a winding indicator ($300), a minute repeater ($465), and a combined minute repeater and split-seconds chronograph ($650). In today's dollars, the prices would be about The Dietrich Gruen watches had their own unique family of fully-adjusted movements, which are designed differently from Gruen's other movement lines. Cases came in several shapes, including round, octagonal and square. Later models were housed in Pentagon cases. When the UltraThin movement was introduced, it became part of the Dietrich Gruen line. 1911 also marked the debut of Gruen's first national advertising campaign. A very early adopter of such advertising, the Gruens had the sophistication, under the guidance of the J. Walter Thompson agency, not to expect quick results. The strategy was to build an image for the Gruen brand name slowly over many years. | |

|

Fading history | |

|

Problems and confusion with Gruen's early history started after Dietrich's death. I believe that this is partly because Gruen history was rewritten by the company for marketing and PR purposes, and partly because the early history was genuinely forgotten.

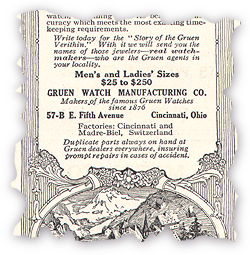

Although the company was started by Dietrich and Fred in 1894, by 1900 they were claiming 1876 as a founding date (this is the year the Columbus Watch Company was founded). Starting in 1915, Gruen's advertising used 1874 instead of 1876. 1874 has remained Gruen's official founding date ever since; the company that makes quartz "Gruen" watches today still stamps "since 1874" on the boxes. Right: A detail from a 1913 ad. Note that it claims 1876 as Gruen's founding date. The ad's headline (not shown) spells the company name For marketing reasons, the Gruen Watch Company wanted to take credit for what Dietrich Gruen had achieved prior to 1894. To this end, they absorbed the founding date and the early history of the Columbus Watch Company into their own official story, but never mentioned the earlier company by name. This practice is followed by many watch companies, most notably in Switzerland. While some Swiss watch companies may claim founding dates as far back as the 1700s, few can actually demonstrate a genuine, continuous history going back that far in time. (The modern Blancpain company, which claims a 1735 founding date, is actually about 20 years old). In an industry that emphasizes long traditions, most watch companies claim the oldest date that they can possibly justify. Many venerable company names, long defunct, have been revived in recent years, and along with the brand name comes the venerable founding date of the original. Beyond the founding date, there are problems with the official company timeline. The 1929 dealer's catalog claims that Gruen (actually the Columbus Watch Company) had introduced stemwind watches to the U.S. market in 1878 and 16-size watches in 1880. Actually, Dietrich seems to have been making them earlier then this: Columbus watch serial number 572, in the museum at the American Watchmakers Institute, is both 16-size and stemwind; number 4277 is also 16-size and stemwind. An earlier Gruen publication claims that Dietrich offered 16-size watches as early as 1874 (but substitute 1876 for 1874); this seems more accurate, based on the evidence provided by actual watches. I've found two timelines of Gruen history. One is in the little 1918 book, A Worthy Company of Watchmakers (published by Gruen), the other is in the 1929 Gruen dealer's catalog. These dates and company names are given in both timelines: 1874: Dietrich Gruen Early in my research I had been pleased to disover this timeline and it formed the skeleton of my original outline of Gruen history. I found no reason to question it; how could the company itself be wrong about these dates? However, with more research it became clear that this timeline is not completely accurate. The company name between 1876 and 1894 should be the Columbus Watch Manufacturing Company/Columbus Watch Company. The company was reorganized in 1882, but this is not shown. The 1879 date for Gruen's partnership with Savage is interesting, but Gruen and Savage were already partners before this. The first time that the company shows up in a Columbus street directory, in 1878, Dietrich is listed as president and Savage as secretary and treasurer, so Savage was part of the company from the start (and it had been Savage who financed the partnership). Deitrich does not show up in the Columbus street directory until 1877; in that year Deitrich is listed as a watchmaker and Savage is listed as a wholesale jeweler by professsion. The next year, 1878, they are both listed as officers of the Columbus Watch Manufacturing Company. These old street directories date from before the telephone. The goal was to document the name, address and occupation of every adult male. The listings were compiled by individuals going door-to-door and neighborhood-to-neighborhood and talking to each resident. This would be a time-consuming process; by the time the survey was completed and the data was compiled, edited, typeset and published, some of it would already be out-of-date. If the partnership was formed in 1876 it might not show up in the 1877 directory but it should definitely be in the 1878 directory — and it is. A different interpretation could be that the official timeline shows Dietrich working on his own before his partnership with Savage; if the second date were 1876 instead of 1879, this would fit. 1879 would have been the third year of their partnership, however, so this is still puzzling. If something significant did happen in 1879, I don’t know what it would have been. Around this time, the move to the basement of Exchange Bank took place. The 1911 change to "Gruen Watch Maker's Guild" was not an actual name or organizational change; the 'Gruen Guild' theme was simply part of a long, ongoing marketing campaign that was started in 1911 (see the 1917 page). The true significance of 1911 was that control of the company passed to Fred upon Dietrich's death. The 1929 catalog includes a chart showing historically-significant Gruen watches, but it shows at least one watch that is obviously incorrect, in order to avoid showing a watch with the Columbus name on the dial. I believe that 1876 is the correct date for the start of the Columbus Watch Company, since this is the founding date that was used by the company and those who wrote about them in the 1800s, and because 1876 was used by Gruen before 1915. I believe that the 1874 date is simply the pinion patent date, and was (and is) used because it is the earliest evidence of Dietrich Gruen's watchmaking activities. Eugene Fuller, in The Priceless Possession of a Few, reached the opposite conclusion. He chose to give the later company records greater weight, while I have chosen to give the earlier material, closer in time to the actual events, precedence. The fact that 1876 was used while Dietrich was alive and in charge of the company is a compelling argument. Some very early Columbus watches have an 1874 patent notice on the dial or movement, but this is the patent date, not the date the watch was made. I also feel that the later Gruen Watch Company's public relations and advertising people would have wanted to present a simpler and less-confusing early history. It is, of course, possible that Dietrich Gruen made or finished earlier watches before starting his company. I am continuing to research this subject. I would encourage readers to be very skeptical about everything in print about the early Columbus Watch Company, including what I've written on these web pages. So much has been lost!

[ 1867 | 1894 | 1904 | 1917 | 1921 | 1922 | 1929 | 1940 ] [ Contents | Intro | Sources | Links | FAQ | Patent | Cover ]

Copyright © 1999-2001 Paul Schliesser

contact

|

|

Right: A Gruen SemiThin from the 1920s, with a gold-filled case. Although originally priced at about two-thirds the cost of a comparable VeriThin, its movement, case and dial are of high quality.

Right: A Gruen SemiThin from the 1920s, with a gold-filled case. Although originally priced at about two-thirds the cost of a comparable VeriThin, its movement, case and dial are of high quality.

A woman's convertible watch made by Gruen in the mid-1910s; 26mm in diameter. This type of watch was the predecessor to the wristwatch, and continued to be made until about 1920. This dial is in Gruen's Louis XIV style, which recalled the look of classic watches from the 1700s.

A woman's convertible watch made by Gruen in the mid-1910s; 26mm in diameter. This type of watch was the predecessor to the wristwatch, and continued to be made until about 1920. This dial is in Gruen's Louis XIV style, which recalled the look of classic watches from the 1700s.

An early Gruen man's wristwatch—date unknown, but I believe this is pre-WWI. The 29mm-diameter case is made of silver, and has a hinged back and inner dust cover just like a pocket watch. The 15-jewel movement was originally designed for a woman's pocket watch. Note that, when wearing it, you must hold your arm vertically to read the time. This was not unusual for early wristwatches, but is awkward, and eventually the dial orientation we use today became standard.

An early Gruen man's wristwatch—date unknown, but I believe this is pre-WWI. The 29mm-diameter case is made of silver, and has a hinged back and inner dust cover just like a pocket watch. The 15-jewel movement was originally designed for a woman's pocket watch. Note that, when wearing it, you must hold your arm vertically to read the time. This was not unusual for early wristwatches, but is awkward, and eventually the dial orientation we use today became standard.

Left: 23-jewel Dietrich Gruen with up/down (power reserve) indicator. "A thin model watch pronounced by jewelers and horological experts to be the World's Finest Pocket Timepiece." (Photo by Jack Goldberg)

Left: 23-jewel Dietrich Gruen with up/down (power reserve) indicator. "A thin model watch pronounced by jewelers and horological experts to be the World's Finest Pocket Timepiece." (Photo by Jack Goldberg)