|

1922: Consolidation of The Gruen Watch Company | |

| There were three Gruen companies: D. Gruen, Sons & Company; The Gruen National Watch Case Company of Cincinnati; and The Gruen Watch Manufacturing Company of Biel, Switzerland. In 1922 all three businesses were merged to form the Gruen Watch Company, with Fred as President. | |

|

1924: The 50th Anniversary Watch "we present the supreme example of our art and science" | |

|

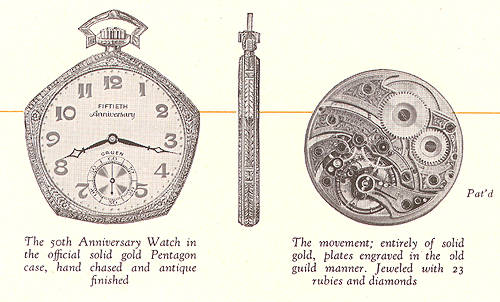

In 1924, Gruen released a special pocket watch in an edition of 600 to commemorate their 50th anniversary (50 years since Dietrich Gruen's 1874 pinion patent). Each watch in the 600 represented one month of the 50 years. This was one of the most extravagant and expensive watches that had ever been made. Gruen promoted this watch as, "the priceless possession of a few." The plates, bridges and wheels were made of gold, with ornate foliage patterns engraved into their surfaces. The original plan was to use 14k gold for the plates, but they were changed to 12k for engineering reasons. The 23-jewel movement (which included faceted diamond cap jewels on the balance and escape wheels) was "extra-Precision," adjusted to 8 positions and temperature.

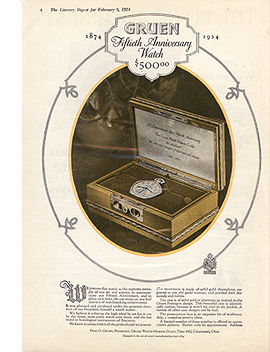

Above: Gruen 50th Anniversary watch number 513, in a white gold case. This example is from the first series of 600. The close-up shows the beautiful finishing and engraving on its movement. Every screw fits into a steel sleeve in the solid 12k gold plates. The cap jewels on the balance and escape wheels are faceted diamonds. (Both photos by, and courtesy of, Jack Goldberg.) Most watches were housed in an 18k yellow or green gold Gruen Pentagon case, but the customer was invited to order his own custom case. (Gruen means "green" in German; especially during the 1920s the company seems to have tried to popularize green gold, although white gold was much more fashionable at the time.) Externally the Anniversary looks similar to Gruen's other Pentagon models, which lent prestige to and helped sales of these other models—this was part of Gruen's deliberate marketing strategy. Included was a magnificent leather-covered, locking jewelry box with gold and brass fittings. The standard model cost $500 USD, the equivalent of about $15,000 USD today, but many owners chose custom cases at a much higher price. The more ostentatious owner could even choose a solid platinum case studded with diamonds.

Fred Gruen gave the design, manufacturing and sales of this watch his personal attention, and everything was handled with great ceremony. The only way potential customers could even arrange to see the watch was to make a request in writing to Fred Gruen, personally. The Anniversary watches were not distributed to, or displayed in, any stores. After the sale, the name of the owner was recorded in a large leather-bound book at Time Hill. Many of these watches were used for special presentations—General John J. "Black Jack" Pershing (commander of the U.S. forces in World War I) was given an Anniversary watch when he retired from the Army. Other notable owners include the executives of auto companies Dodge, Ford and Nash, several newspaper publishers including Dallas publisher George Dealy, governors, senators, and noted aviators Howard Hughes and Eddie Rickenbacker. Since the movement was so highly decorated, display backs were an option, but many of these watches were sold with solid backs to hold elaborate presentation engravings. When production of the 50th Anniversary ended, it was discovered that there were enough parts to build an additional 50 movements. While watches in the first series each represent one month and were numbered 1 to 600, each of the second series represents one year, and were numbered 01 to 050 (the "0" before the number indicates the second series), making a total edition of 650.

Above: Detail from the Gruen 1929 Dealer's catalog. At a casual glance, the watch doesn't look much different from a typical Pentagon model. Part of the strategy behind this watch was for it to lend its status to the rest of Gruen's Pentagon line. The Waltham and Howard companies had done similar very expensive watches—there was a sort of competition in the teens and early 1920s to see which company could claim to offer the most expensive, most prestigious and highest quality pocket watch in America. The editions of these expensive watches often took years to sell out. By the early 1930s, Gruen had sold less than half of the Anniversary watches. Since customers were encouraged to customize these watches, the movements were stored at Time Hill and were not cased until an order was placed. During the lean years of the Great Depression and later, most of the remaining movements were sold off at bargain prices in 14k or gold-filled cases. The last four 50th Anniversary movements were still in stock in 1958 (Gruen's 84th anniversary). Three of these were sold and one was retained by the company for historical reasons. | |

|

1925: The Quadron "the nearest approach to pocket watch accuracy for the wrist" | |

|

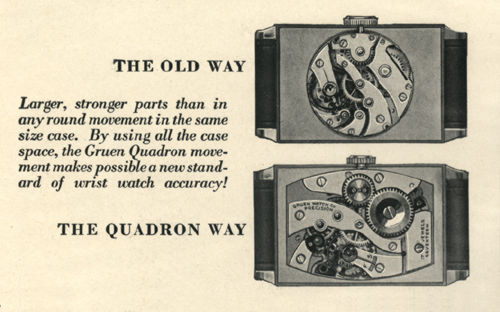

Above: Detail from a 1930 ad. Having been used by soldiers and pilots, the wristwatch started to look more acceptably masculine to civilians after the War. Many ads from this era were careful to refer to men's wristwatches as "strap watches," to avoid the long-held stigma of the wristwatch as a feminine accessory. These ads often listed rugged, manly professions and activities for which the strap watch was suited. Just as was true for women, styles for men's wristwatches quickly moved to tonneaus and rectangles, and away from the round shape associated with pocketwatches. Round wristwatches would not become popular again until the 1950s. In 1925, Gruen introduced the men's Quadron. Similar in concept to the women's Cartouche models, these were rectangular watches containing very high-quality 15-j or 17-j tonneau-shaped movements. A larger movement is generally more reliable and accurate, and is generally more rugged, than a smaller one of the same quality, so the Gruen Cartouche and Quadron, with their case-filling, purpose-built movements performed much better than the small, round movements used by most of their competitors at the time. Round movements were still used in the less expensive rectangular Gruen wristwatches.

Above: A typical Quadron model from the late 1920s, with a white gold-filled case and luminous hands and dial. This particular model has a 'crown guard' case—note how the slight projections on the side of the case protect the winding crown from knocks. According to their advertising, Gruen submitted a consecutive run of 200 ordinary Quadron movements for observatory chronometer tests in Switzerland. There was not a category for wristwatches in 1925, so they were tested to pocket watch standards. Each of the 200 were granted a certificate for timekeeping excellence, which Fred Gruen believed to be a record at the time. These were the earliest American wristwatches to qualify as serious timekeeping instruments on par with a pocket watch. The efforts of companies like Gruen during this era helped change the public's negative attitude towards men's wristwatches.

Above: A white-gold Quadron (left) with radium dial numbers and hands, shown next to a women’s Cartouche (right) with a blue sapphire crown on a black silk ribbon with adjustable buckle. |

|

|

The Baguette "as narrow as a cigarette" | |

| A much smaller rectangular women's watch was the Baguette, with an exceptionally tiny 17-jewel movement. Like the Cartouche, these movements filled the small cases. These were the more expensive Gruen women's watches in the late 1920s and early 1930s—many had diamond-encrusted 14k or platinum cases and bracelets. | |

|

1928: The Techni-Quadron "for exact time in seconds" | |

The famous Techni-Quadron "doctor's watches" are so-called because the large seconds dial was handy for timing a patient's pulse. These were not sold only to doctors, however. The watch was advertised as a timepiece for technicians and "radio and mechanical engineers"—anyone who needed to measure time in seconds. The 877 movement, manufactured by Aegler in Biel, was also used in the Rolex Prince; this unusual movement gives the watch its distinctive "dual dial" design. Hours and minutes are confined to the upper half of the dial, while the entire lower dial is dedicated to seconds. The Techni-Quadron provided a useful alternative to the tiny seconds hands on most watches from this era, which can be as little as 2mm (one tenth of an inch) long, and are not practical to use for timing. Left: All Techni-Quadron models have a long case and a large seconds subdial, as large (or nearly as large) as the hour/minute portion of the dial. The "dual dial" layout is a distinctive feature of this line. This particular watch is slightly unusual—most have dials that are more functional and less ornate. Compare this dial to the catalog illustration below, which is more typical. (Photo courtesy of Jack Goldberg.) Left: All Techni-Quadron models have a long case and a large seconds subdial, as large (or nearly as large) as the hour/minute portion of the dial. The "dual dial" layout is a distinctive feature of this line. This particular watch is slightly unusual—most have dials that are more functional and less ornate. Compare this dial to the catalog illustration below, which is more typical. (Photo courtesy of Jack Goldberg.)

Other rectangular Gruen models from this era, even if they have large seconds subdials, are not doctor's watches. The Techni-Quadron does not have the hour and minute hands attached at the center of the dial— as other watches do—on the contrary, these hands are attached above where the crown enters the case. The seconds are in their own subdial, which is symetrically placed outside of and below the hours/minutes portion of the dial. Because these watches are sought after by collectors, other models are often represented as Gruen "doctor's watches" when offered for sale. The Techni-Quadrons were extremely accurate, and like other Quadron models, did well in European chronometer tests. Some Techni-Quadron models originally came with "expanding buckles." These look nearly identical to modern deployant buckles, but their purpose was different. With the buckle closed and locked, the watch could be worn normally. However, if the buckle was unlatched, making the strap loose, the wearer could slide the watch up the arm until it fit snugly just above the elbow, keeping the hands and wrists free. A 1929 advertising photo shows a doctor wearing his watch this way. These buckles were available on metal mesh bracelets or leather straps. A smaller version of this buckle was offered for women.

Above: An illustration of a Techi-Quadron with an "expanding buckle" from the 1929 catalog. The buckle allows the watch to be worn either normally, or above the elbow, as shown in the photo. Another interesting Quadron wrist attachment was the "Ben Hur" bracelet, made by Wadsworth. This was a perfectly smooth, gold-filled, single-piece flexible metal strip, with a concealed clasp. When worn, it looked like the watch was held by a shiny wrist band of solid metal. After Gruen moved all production to the Precision Factory and stopped buying movements from Aegler, they made some dual-dial watches that are superficially similar to the Techni-Quadron, using modified versions of Gruen's calibre 500. | |

|

Gruen, Rolex and Aegler | |

|

One of the most deeply-held myths about Gruen is that Gruen and Rolex at one time manufactured movements for each other's watches. This is not true, although both firms did use some of the same movements—the best known examples are the Gruen Techi-Quadron and its twin, the Rolex Prince. In reality, these movements were manufactured by a third company, Aegler, who was a very close neighbor to the Gruen Precision Factory.

Above: The Aegler factory in Biel. Aegler made movements for Rolex (which had no manufacturing capability at the time), and this building is the main Rolex factory today. Up until the early 1930s, Aegler was partly owned by Gruen. Gruen and Rolex were Aegler's biggest customers, and were both large shareholders as well—the full company name at one time was, Aegler, Societe Anonyme, Fabrique des Montres Rolex & Gruen Guild A. Gruen and Rolex both occasionally showed pictures of the huge Aegler factory in their advertising, making the implication that this was a Gruen- or Rolex-owned facility, although ownership at the time was divided among Gruen, Rolex and Aegler itself. Gruen sold their Aegler shares in the 1930s, after they moved all production to the Precision Factory. After this time, Aegler became increasingly tied to Rolex through the sale of stock. Today, the main Rolex building in Biel is the old Aegler factory, and though it is now owned by Rolex, it is still run by the Aegler family.

[ 1867 | 1894 | 1904 | 1917 | 1921 | 1922 | 1929 | 1940 ] [ Contents | Intro | Sources | Links | FAQ | Patent | Cover ]

Copyright © 1999-2001 Paul Schliesser

contact

| |

Right: Full page advertisement from the February 9, 1924 issue of the Literary Digest. Note the leather-covered wooden box with gold and brass fittings.

Right: Full page advertisement from the February 9, 1924 issue of the Literary Digest. Note the leather-covered wooden box with gold and brass fittings.