|

The Great Depression | |

|

By the early 1930s, men's wristwatches had overtaken pocket watches in popularity, although wristwatches were not yet considered appropriate for formal dress. Gruen pointed out in advertising that if a customer wanted to be properly fashionable, he needed to own both a wristwatch and a pocket watch. They helpfully quoted authorities on etiquette who supported this claim. Gruen even offered watch boxes that held one watch of each type.

Right: The U.S. economy was staggering under the effects of the Great Depression—watch sales in the U.S. had gone from over five million to around 800,000 per year, and most of these were in the lower price range, not the upscale watches that Gruen had sold previously. After 1929, Gruen began to offer many less expensive watches than they had before, and ad headlines started to mention value and price. The shrinking market and reduced output is probably what prompted Gruen to divest themselves of ties to Aegler and to bring all outside movement production into the Precision Factory. In 1935 Fred Gruen, now 63 years old, became Chairman of the Board and Benjamin S. Katz was brought in as President of the Gruen Watch Company. In 1935, Gruen was about $1.8 million USD (roughly $36 million USD today) in debt; nervous stockholders and investors were behind the change. Katz came from Katz & Ogush in New York, a watch case company that made 14k, 18k and platinum cases for lady's watches. Fred would retire in 1940, but continued to sit on the board for the rest of his life. Gruen was not the only company to suffer—some of their competitors went out of business entirely. As bad as things were for Gruen, they were actually in a strong position relative to others in the U.S. watch industry. Hardest-hit were companies which had failed to move into the wristwatch market, like Howard, Hampden and South Bend, all three of which folded during this time. (South Bend had been the last surviving remnant of Dietrich Gruen's old Columbus Watch Company.) | |

|

1931: The Carré "the very chic Gruen that clicks open at a finger touch" | |

Above: Detail from a 1931 ad. Note that this Carré has luminous hands and dial numbers, making it convenient to use as a bedside travel clock. The Carré, an innovative and unusual watch and a wonderful example of Art Deco design, had three intended uses: as a man's pocket watch, as a woman's purse watch, and as a small, portable table clock. The case was available with or without an attachment for a chain. Sliding the button on the side causes the case to spring open, revealing the diamond-shaped watch inside. The clever case design would stand upright when opened, making it useful as a small desk or bedside table clock, a convenient accessory for traveling. The Carré contains a round, 15-jewel movement similar to those used in early-1930s men's wristwatches.

The watch was available in a number of finishes, from solid 14k gold to nickle. The outside case came in a number of colorful variations, including two-tone lacquer finishes (among them orange/black and green/cream; both with bright nickle trim), a number of exotic and colorful leather coverings, with engraved patterns, or with geometic patterns done in enamel inlay. As clever and elegant as the Carré is, it seems not to have been a big commercial success. Its last appearance in advertising was in 1934, three years after its introduction. Prices started at $55 USD, and solid gold models were $125 USD (roughly $1375 to $3175 USD today). Perhaps if it had not been released during the early years of the Great Depression, it would have found a larger audience—the early 1930s were not the best time to sell a pricely luxury item like this. | |

|

1935: The Curvex "your curved wrist deserves the world's only truly curved watch" | |

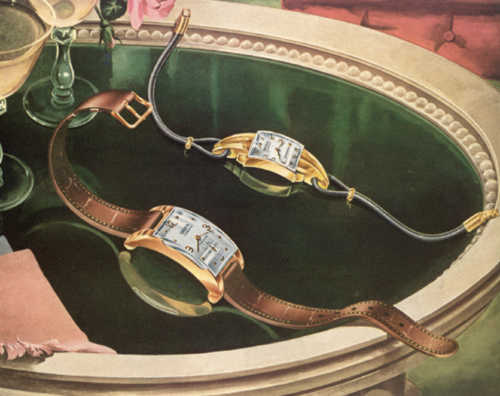

Above: A detail from a 1944 ad showing a man's model, the Curvex Governor, and a woman's model, the Curvex Queen. The most famous Gruen wristwatch was the Curvex. These watches are one of the greatest examples of 1930s streamlined design. The patent for the movement was applied for (in both Switzerland and the U.S.) in 1929. U.S. patent 1,855,952 was granted on April 26, 1932 to Emile Frey of Bienne, Switzerland, but assigned to the Gruen Watch Company. It was later reissued as Re. 20,480 under Gruen President Benjamin Katz's name in 1937, after Frey's death. The first watches went on sale in 1935.

During the mid-1930s, the fashion was for longer and more curved rectangular watches for men. However, the thinness and curve of the case was limited by the need to put a flat movement inside. As the case got thinner and more curved, the only conventional option was to use a smaller and smaller movement. By a clever internal arrangement of the wheels and bridges, Gruen solved this problem by building a curved movement—this allowed them to put a bigger and more reliable movement into a thinner and more curved case than their competitors could. Since the design was patented, these curved movements were exclusive to Gruen. The Curvex was very successful, and was soon followed by women's models.

There were four men's Curvex movements. The original 1935 model was the long, thin calibre 311. This was soon replaced by the more curved 330 (1937), also long and thin. As fashions changed, later Curvex models used the short, squarish-oval 440 (1940) and the short and wide 370 (1948). Watches with the 330 were called Custom Curved and 370 models were called Curvametric in Gruen advertising, although the dials are all marked simply Curvex and Precision. Any man's watch that does not contain one of these four movements is not a Curvex, no matter what is on the dial or how persuasive a seller might be. Dials can be redone or swapped with another watch; it's the movement inside that counts. Having said this, many collectors have an obsession with the Curvex and ignore many of the other interesting models. Gruen was responsible for some of the most creative watch styling of the 1930s, and produced many other unusual and elegant designs during this period.

Prior to the Curvex, Gruen made other curved wristwatches, many using long, thin movements like calibre 500. Although sellers and collectors will often refer to any rectangular, curved watch (Gruen or otherwise) as a Curvex, this is incorrect—the name was a Gruen trademark, and referred to the movement, not the case design. Curved models incorporating variations of calibre 500 were kept in Gruen's line as lower-cost alternatives to the Curvex. Although the 500 and 501 movements are related to the 311, and were made in curved versions (a "C" after the model number is for "curved") and have many parts in common with the 311, they are 15-jewel movements and are not Precision grade. These watches cost around $35 USD. All Curvex models have 17 jewels and are Precision grade; the cheapest Curvex prices started around $50 USD, and many models cost significantly more.

In 1936 the first Curvex models for women were produced, with the tiny calibre 520 curved movement. The Curvex, for both men and women, was Gruen's flagship product from the mid 1930s until the late 1940s. The last models were made around 1954.

Above and below: Women’s watches in the 1930s and 1940s, including the Curvex, were extremely small.

| |

|

The price of a good watch | |

| In this age of cheap quartz watches, it's easy to forget how expensive a quality mechanical watch once was. In the mid-1930s, prices for men's Curvexes started at $50 USD for gold filled models, which is the equivalent of about $1000 USD today. Although cheaper watches could be purchased in the 1930s, the least-expensive watches with jeweled movements cost around $25 USD, or $500 USD in today's dollars. Unlike today, when the cheapest quartz watch keeps time nearly as well as the most expensive luxury watch, the durability and accuracy of a watch were directly related to price. Pin-lever watches from companies like Ingraham and Ingersoll (which would later become Timex) were much cheaper, but might run several minutes fast or slow and wore out quickly because they lacked jeweled bearings. (Pin-levers were the same type of movement used in inexpensive children's and novelty watches.) In the 1930s, many workers made less than $3 USD per day, so even the cheapest jeweled watch would have been a major purchase. Because young people starting their adult lives could use a good watch, but could seldom afford one, a watch was the traditional gift from parents to children at graduation. Gruen, as well as their competitors, always ran special advertisements at graduation time. | |

|

1937: The Ristside driver's watches "in direct line of vision when driving or working" | |

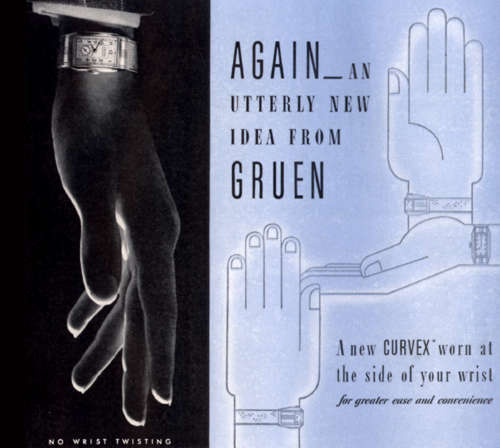

Above: Detail from the April, 1938 ad, the first national advertisement for the "driver's" watch (shown is the Curvex Lord). Previous ads had only hinted at what this watch would look like. Among the rarest and most collectable of Gruen wristwatches are the "driver's" models—the Ristside ("wrist side") and Curvex-Ristside models. Designed to be worn on the side of the wrist, they place the dial in line with the base of the thumb. When driving, you can see the dial without turning your arm or letting go of the steering wheel.

Hamilton and other companies quickly brought out driver's models of their own. These are some of the most fascinating, unusual and collectable wristwatches of the 1930s. The Ristside models feel very strange to wear the first time you try one on—the watch feels as though it's projecting out of your wrist bone. Reading the time is very convenient, however—you don't need to twist your hand palm-down to see the dial, you simply bend your elbow and leave your hand in its relaxed position. This feels very comfortable and natural. A normal leather strap is awkward to use with these watches, because the buckle ends up on the little-finger side of the wrist, opposite the watch. Some originally had special straps, which were extremely long on the buckle end, but very short on the other end. Although they look strange, when worn these straps correctly place that the buckle on the underside of the wrist. Ads show many Ristside models on a scissors-type expansion bracelet. Since these have no buckle, they are espeically convenient to wear with this type of watch.

Interestingly, the Ristside models seem to have been marketed mainly to young people, and tended to show up in ads around graduation time. Several models were made in 1937-38, then after a long absence, the Curvex-Ristside Fraternity showed up in 1950. Most Curvex-Ristside models use 330 Curvex movements. One model, the Varsity, is not a Curvex, but uses Gruen calibre 401. The Curvex-Ristside Fraternity which had long, stepped, hinged lugs, used the 440 Curvex. (The Fraternity is often described as the "angel wing" driver's watch) Only the Fraternity and one other very similar model have hinged lugs. Gruen made very few driver's models; the line was apparently not commercially successful. They were introduced with great fanfare, then quickly vanished again. Because these models are so sought after, you often see other Gruens incorrectly identified as driver's watches. Some sellers seem to think any watch with hinged or hidden lugs is a driver's model, even if it is round! The style of strap attachment does not make a watch a driver's model. The true driver's watches are all rectangular, but have much more extreme curves than a normal Curvex. Except for the two models with hinged lugs, these watches are impossible to wear normally on top of the wrist. The modern Gruen company made gold-plated reproductions of several classic Curvex models in the 1990s, at least one of which was a driver's model. All contain quartz movements. If you are looking for a vintage Curvex, beware of buyers misrepresenting these reproductions as the real thing. | |

|

1938: The Veri-Thin wristwatches "gloriously styled— and so practical!" | |

Above: A size comparison between an Ingraham Wrist-O-Crat (top), an inexpensive 1930s watch, and a typical man’s Veri-Thin model (bottom). Continuing the success of their VeriThin pocket watches, Gruen also launched a series of Veri-Thin wristwatches. Contemporary Curvex and Veri-Thin movements often are closely related, and can share many parts. By the 1940s, most Gruen wristwatches were either Veri-Thin or Curvex models, although a few cheaper models with older movements were still produced. Like the Curvex, the Veri-Thin was developed to honestly fill fashionable watch case shapes, and was an alternative to using a smaller, less-durable and less-reliable movement. Veri-Thin calibres are shaped to be thicker in the middle and thinner around the outside edges. Their dials are curved or domed, and the movement bulges up into the dial shape. The shape of movement, dial and case is designed to present a very thin edge when viewed at an angle, and to disguise the fact that the watch is thicker in the center. These styling tricks are very effective—many of these models look impressively thin and flat when worn. As styles changed, later models often had boxy, flat sides, and did not have the thin, flat look of the early models. Some Veri-Thin models have curved cases and most have curved dials, so it is common see these incorrectly represented as Curvex models, since Curvexes command higher prices. There are a huge variety of Veri-Thin models, which include some of Gruen's most outrageous designs. There is no need to misrepresent these watches—they are interesting in their own right. Note: Gruen spelled the early pocket watch name (pre-1930) as one word—VeriThin. The pocket watches from the 1930s and later and the wristwatch name always have a hyphen—Veri-Thin.

[ 1867 | 1894 | 1904 | 1917 | 1921 | 1922 | 1929 | 1940 ] [ Contents | Intro | Sources | Links | FAQ | Patent | Cover ]

Copyright © 1999-2001 Paul Schliesser contact

| |

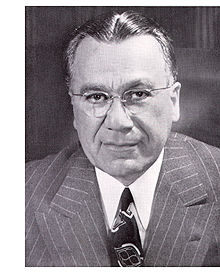

Benjamin Samuel Katz (1892-1969), who succeeded Fred Gruen as President of the Gruen Watch Company in 1935. Photo from the 1940s.

Benjamin Samuel Katz (1892-1969), who succeeded Fred Gruen as President of the Gruen Watch Company in 1935. Photo from the 1940s.

Right: Diagram from a 1938 advertisement, showing the Curvex concept.

Right: Diagram from a 1938 advertisement, showing the Curvex concept.

Left: The 1938 Curvex Coronet (original price $50). Note the side view: the case is too short and bends much too sharply for it to be worn like a normal watch. (Both photos by Jack Goldberg.)

Left: The 1938 Curvex Coronet (original price $50). Note the side view: the case is too short and bends much too sharply for it to be worn like a normal watch. (Both photos by Jack Goldberg.)

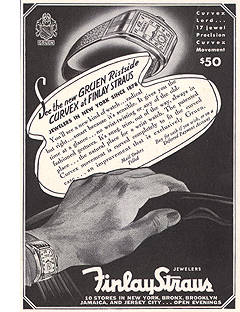

Right: A 1937 Jeweler's ad for the Curvex Lord, one of the first Ristside models. The illustration exaggerates the thinness of the watch, which is identical in form to the Curvex Coronet, above. The main difference between the two models is that the Curvex Lord has a decorative pattern of parallel lines on its case. Another model, the Curvex Admiral, has a plain, undecorated case. All three models use the Curvex 330 movement.

Right: A 1937 Jeweler's ad for the Curvex Lord, one of the first Ristside models. The illustration exaggerates the thinness of the watch, which is identical in form to the Curvex Coronet, above. The main difference between the two models is that the Curvex Lord has a decorative pattern of parallel lines on its case. Another model, the Curvex Admiral, has a plain, undecorated case. All three models use the Curvex 330 movement.